A Framework for Thinking About Carbon Net-Zero Commitments

October 2022

The debate over carbon net-zero strategies and their implications for investors and asset owners is intensifying. To clarify the implications of asset owners making a net-zero commitment, we believe it is useful to answer the basic questions of why, how, and when?

Why?

Climate change is happening, human activity contributes to global warming. The Paris Agreement is a global effort to limit warming to well below 2’C (ideally below 1.5’ C), which translates into a goal for human activities to peak CO2 emissions as soon as possible and collectively emit net-zero CO2 (and other warming gases) by 2050. That collective effort by economic and political entities is substantially changing our economic system and, in turn, affecting portfolio returns. By taking the decarbonisation trend into consideration, net-zero portfolios are expected to avoid stranded asset and carbon cost risks and, ultimately, maximise risk-adjusted returns.

How?

Three key strategies to achieve net-zero portfolios are: 1. Engagement, 2. Divestment, and 3. Offset.

1. Engagement

Through this strategy, investment managers interact with investee companies’ leadership teams with the goal to:

- Assess corporate readiness to the changes in train

- Evaluate the plausibility of corporate assumptions, plans, and disclosures (CAPEX, margins, competitiveness, regulation, etc.)

- Influence the pace of change with the aim to ultimately improve portfolio returns as companies better prepared to face the climate challenge are likely to outperform laggards

This is the strategy currently employed by Spheria: we routinely engage with investee companies on climate change and other ESG themes. For companies in hard to abate sectors, climate change takes the lion part of our ESG attention. We demand disclosure improvements in every interaction and are official Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) supporters. We engage cooperatively with other investors on climate and other ESG themes. Spheria is a member of Climate Action 100+ (CA100+), Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking (IAST), and the Pinnacle Investment Management ESG Working Group. Our engagement work informs our analysis and enhances our understanding of investee companies’ risk and opportunity set. Our ESG research affects how we value stocks and make investment decisions.

In most cases one can not demonstrate causality (e.g. that company X did Y because we asked them to, during meeting Z) and, unless it spills into voting at AGMs and/or a divestment decision. Engagement is barely visible: only disclosed in broad terms in sporadic ESG reports and presentations. The quality and effectiveness of engagement efforts are often hard to assess by clients; as such, it requires trust. While asset owners and asset consultants can vet funds managers and satisfy themselves that this work is done to good standards, convincing superannuation members may prove harder due to the lack of headline grabbing press releases and sweeping statements about one’s position and actions.

Despite its unglamorous status, engagement is arguably the most effective tool to maximise risk-adjusted returns through the above mentioned virtuous cycle between engagement, analysis, and investment decisions. It allows funds managers to stay clear from sector exclusions, which have the potential to skew returns (more on that later), and makes full use of the investment manager, who is empowered to assess investment opportunities to the best of his/ her ability including climate change risks in their thinking without the added constraint of having to meet specific targets. It requires trust because it is in effect a delegation of responsibility for the handling of carbon risk to the funds manager.

Engagement is also the most effective tool to further the climate agenda as investors’ influence over corporations only exists for as long as we remain shareholders. Once we divest, why should corporates care about what we think or want, and why should they spend time listening to what we have to say? Divesting simply changes the ownership of the problem company, it does not influence its actions.

Despite the efforts of respected climate advocates1, partly because ESG is an amorphous term that means different things to different people and because of inconsistent messaging on how it is done and how it affects investment performance, we don’t believe that the nuances and implications of engagement and divestiture are widely understood by the general public. Climate change is a complex problem and issues relating to hard to abate sectors and the pace of a just transition are often lost in the fog of war of a heated debate. Many people concerned about climate change (and some NGOs!) seem to believe -wrongly in our view – that them not owning carbon emitting companies contributes to solving climate change and carries negligible risk to investment performance.

2. Divestment

Divestment is the strategy the public normally thinks of when thinking of ethical investment: an ethical fund becomes ethical by excluding pornography, tobacco, and landmines (and whatever else is deemed undesirable) from the investible universe. By extension, an asset owner who cares about climate change would exclude high carbon emitters from their portfolios.

Divestment strategies present a few issues:

1. They are ineffective: we have excluded tobacco companies from ethical portfolios for decades and they are still happily vaping away

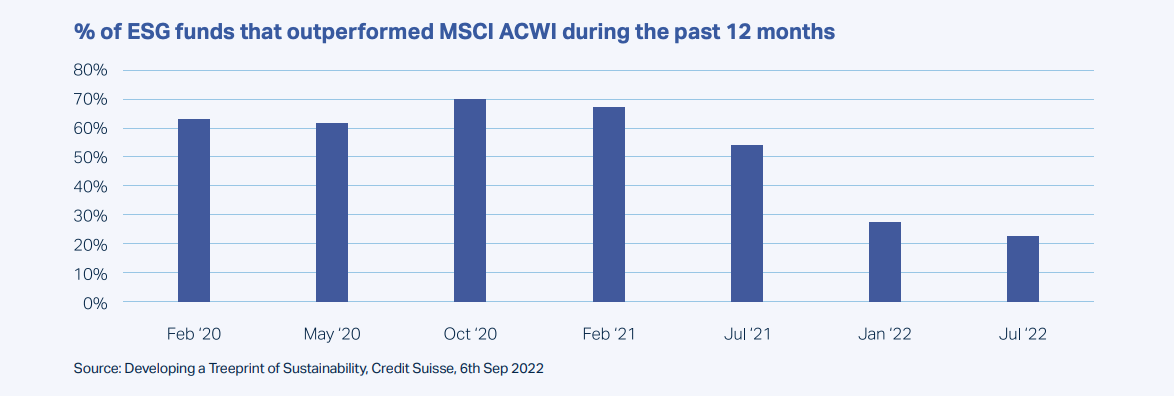

2. They introduce performance biases: while nasty companies are likely to underperform in the long term, if the issue investors have identified is significantly relevant (health for tobacco, climate change for high carbon emitters), they don’t do so on a straight line and portfolios will underperform in periods when the excluded companies outperform. If those periods last for a year or longer, asset owners employing divestment strategies may fall down the ranking APRA prepares for its My Super Performance Test. The current environment characterised by high hydrocarbon prices is a perfect example of the risk that divesting high carbon emitters poses to portfolio performance in the short to medium term. That risk is already visible in the deteriorating ESG funds’ performance, as highlighted by Credit Suisse research in the graph below:

There is an additional difficulty with excluding high carbon emitters and that is that – contrary to tobacco, landmines and pornography – we collectively want the goods that high emitters produce: we want cheap energy, transport, copper, steel, aluminium, cement, and everything else. In cases where green technologies are available and cost-competitive, choosing those instead of high emitting ones is straightforward; when those alternatives are not available, it is unclear what divesting might be able to achieve. Pushing companies to invest more in R&D through corporate engagement seems a more effective strategy than divesting.

3. Offset

The third strategy to achieve net-zero emissions is to buy carbon offsets. Best practice is to employ offsets only when all options to avoid and abate emissions have been exhausted. Carbon offsets should be seen as a tool of last resort to offset those economic activities that emit carbon and we have not worked out how to retool our process to avoid or capture those emissions.

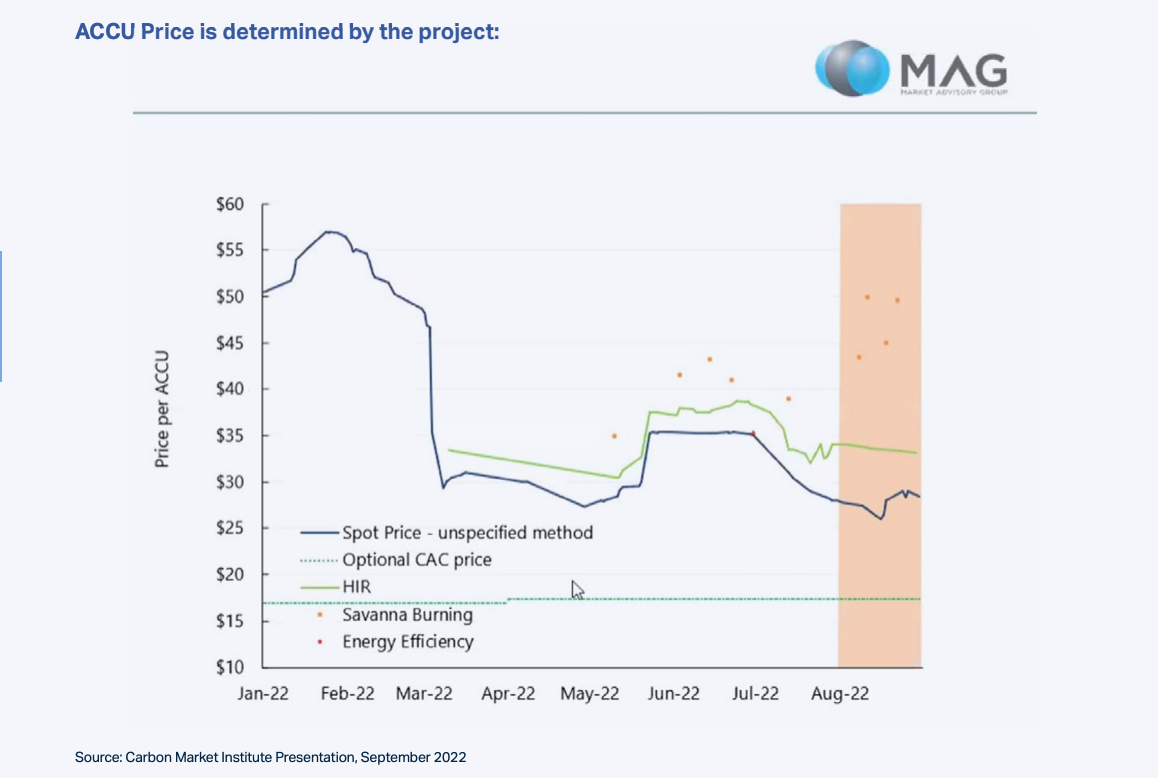

The domestic market for carbon offsets is predominantly voluntary, still in its infancy and marred by complexity and risk. Carbon offsets are non-fungible and the price of offsetting a ton of carbon varies considerably depending on the project one chooses, its perceived legitimacy and the environmental and social co-benefits generated by it.

Below is a chart from a recent Carbon Market Institute presentation. It shows the wide range of ACCU (Australian Carbon Credit Unit) prices depending on the originating project. In September 2022, one could have offset one ton of carbon spending $27 on a generic ACCU or could have spent double that amount offsetting the same one ton of carbon buying a savannah burning ACCU, which being attached to a specific project is more likely to be legitimate and which carries additional social and environmental co-benefits and as such is more desirable and more expensive than a generic one. One could also have offset that same one ton of carbon using an international carbon offset unit, some of which are much cheaper than Australian ACCUs because of their dubious legitimacy.

The cost of voluntarily offset carbon emissions is not negligible. NGS Super estimates that buying Australian carbon offsets to turn their current portfolios net-zero would cost members 0.15% in investment performance2.

Since carbon neutrality is not yet mandated and buying offsets is at this point a Super fund’s voluntary action, it might be wise to consider whether doing so contravene the “sole purpose test” as Super fund trustees might come under scrutiny for arbitrarily adding costs that don’t contribute to performance to their products. One can possibly argue that adding carbon offset costs is a tool to skew portfolio strategy in line with a carbon-constrained future and – as such – acts in the best interest of members by maximising long-term risk-adjusted returns. Is that defensible, though? We’ll need a test case on this issue to find out.

All three strategies carry risk:

Superannuation members may not believe that the engagement work is done and may perceive that strategy as insufficient to combat climate change. While it is arguably a more effective climate strategy than divestiture, the lack of trust in financial institutions likely results in the public preferring the blunter and easier to monitor divestiture strategy.

Divestiture is ineffective against climate change as it does not change corporate behaviour, it simply changes corporate ownership. It also introduces performance biases and exposes Super funds to MySuper Performance Test risks.

Offsets cost Superannuation members money for no apparent performance gain. Can trustees buy them and still pass the sole purpose test? If so, which ones? The cheapest, the best ones for Super Funds branding or something middle of the road decent? Some Superannuation funds currently buy carbon offsets to have net-zero operations (HESTA started the trend in 2019). Operations but – to our knowledge – not portfolios, yet.

When

If one follows the Paris Agreement blueprint, one should aim for carbon neutrality by 2050. The risk of setting such a long-term target is that current leadership may not feel any urgency addressing an issue that will fall outside their tenure and not enough is done to hit that target. Furthermore, delaying action will require more drastic corrections in the future, which increases the risk of missing the target. For those two reasons, corporate paths to net-zero with some integrity all include interim targets (often anchored around 2030).

Recommendation

In our view, this is a question of timing.

John Maynard Keynes once described the stock market as a game where the winner is not the person, who answers questions correctly but the person, who answers first what the majority of participants will.

Maximising risk-adjusted returns in a climate constrained world is no different: one should anticipate the trend and position portfolios ahead of regulatory and societal demands to avoid the risk of holding assets that become stranded, and ill-prepared companies that are likely to underperform. Going too fast though, risks exposing portfolios to periods of underperformance and / or additional carbon offset costs that are not in the best interest of Superannuation members.

One possible strategy could be to set a net-zero target for 2050, an interim 2030 target and a monitoring system that compares portfolio carbon footprints to those of their benchmarks. The carbon risk could then be regularly assessed by investment and leadership teams and appropriate action could be taken, when necessary. A sensible balance between clear guidelines and strategic flexibility should be sought and great care should be paid to communicate clearly and effectively the strategy, its rationale and the metrics used to determine success to all external stakeholders: members, regulators and external funds managers in particular. Any claim with regards to carbon neutrality (and ESG more broadly) will be received with interest and a high level of scrutiny.

Other Resources

What others are doing

- Monash University publishes a Superannuation Net-Zero Tracker, but it has not been updated since September 2020 (https://www.climateworkscentre. org/resource/net-zero-momentum-tracker-superannuation-sector/).

- An Investor Daily article from March 2021 stated that NGS Super has pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2030 while 2050 net-zero emissions goal had been adopted by Aware Super, HESTA, AustralianSuper, IFM Investors, UBS Asset Management and Mercer. The list has likely gotten longer since. Source: “Super fund accelerates race to carbon-neutral”, Investor Daily, 16 March 2021

- Market Forces has a table of hydrocarbon divestment commitments by some funds in the Superannuation sector: https://www.marketforces.org. au/superfunds/.

- Across the ASX200, 95 companies representing 70% of the index market cap have made carbon net-zero pledges3.

- UniSuper represents an interesting case study: they have made a net-zero commitment by 2050 and they offer a number of hydrocarbon-free products amongst their investment options. Despite that, they are under threat of legal action from one of their members (supported by Market Forces), who claims that their investment in Santos is incompatible with their net-zero claims. UniSuper Climate Change Position Statement: https://www.nisuper.com.au/-/media/files/investments/ responsible-investing/climate-change-position-statement-2020. pdf?rev=85abca8f8f7049e8b03a12b292b42c01&hash=040C64433E6EE42C993033D40ACB464F. NGS Super has a net-zero target set for 2030 and has recently announced divestment of their stake in Santos and Woodside arguing that both companies carry high stranded asset risk. Their position is articulated here: https://www.ngssuper.com.au/articles/sustainability/carbon-neutral2030-member-update

1 Go where the emissions are, that discipline of going there and assisting there with the transition is going to make the difference.” Carney made it clear that divestment strategies pushed by some lobby groups and investors – including, on occasions, some of ACSI’s members – would not actually drive the decarbonisation the world needs but simply push the problem on to the shoulders of others. “We can’t get to net zero just by buying all the green assets”. Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, Boris Johnston’s finance adviser for the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow, former Bank of England and Bank of Canada Governor, Director of Canadian asset management giant Brookfield, July 2021

2 Source https://www.ngssuper.com.au/articles/sustainability/carbon-neutral-2030-member-update

3 Source: “Promises, Pathways & Performance: Climate change disclosure in the ASX200”, ACSI, July 2022 https://acsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ WEBSITE-VERSION-ACSI-Climate-Change-Disclosure-in-ASX200-designed-1.pdf 3